The Roaring Twenties

an interactive exploration of the historical soundscape of New York City

By Emily Thompson

Design by Scott Mahoy

Its data is mined through the time-honored techniques of the historian in the archive, through human filtering and detailed close readings.

- Tara McPherson, Editor's Introduction

Alternative views of The Roaring Twenties project data:

All info and conversations from this project page

All info and conversations from this project page

http://vectors.usc.edu/xml/projects/theroaringtwenties_v1.xml

RSS feed of the conversations from this project page

RSS feed of the conversations from this project page

http://vectors.usc.edu/rss/project.rss.php?project=98

http://vectors.usc.edu/xml/projects/theroaringtwenties_v1.xml

http://vectors.usc.edu/rss/project.rss.php?project=98

Editor Introduction

[NOTE: Due to Adobe's deprecation of Flash, the original version of this project no longer works. A revised version, however, is available.]A visitor to my home in Los Angeles recently commented on the noisiness of my neighborhood. I was surprised by this, as I tend to think of my slice of LA as a fairly quiet one. I then began to listen with more care, and sounds I had grown accustomed to came gradually into focus: traffic moving along a nearby busy street, an occasional siren or helicopter, even the howls of the coyotes camped out by the reservoir. Still, I thought to myself, it is not like New York. As much as I love that city, I am always surprised by how loud it is and have learned to ask for hotel rooms far above street level. The cacophony is at once energizing and exhausting. In The Roaring 'Twenties, Emily Thompson reminds us that it is also deeply historical and contextual.

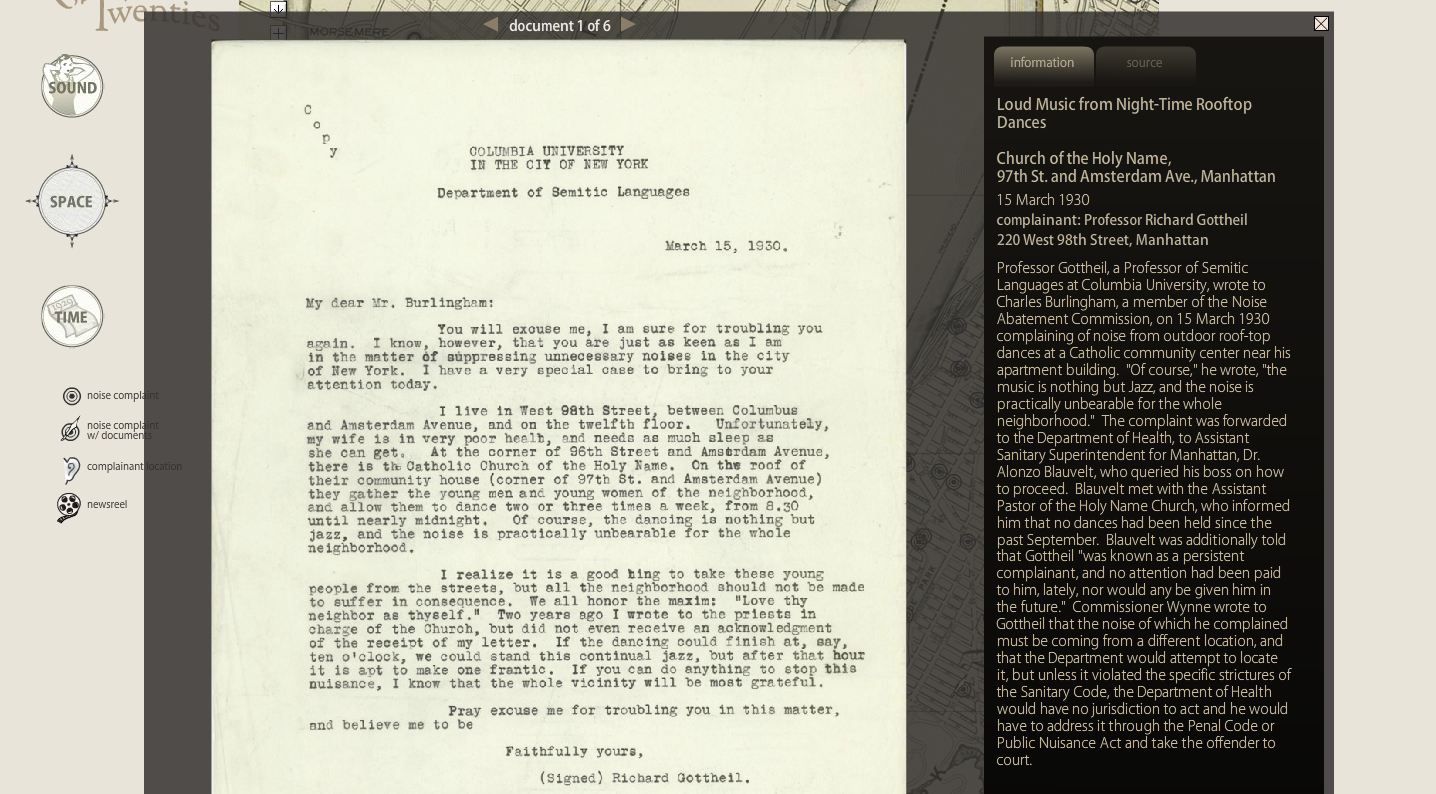

Thompson is a historian of sound, a member of a burgeoning community of scholars who turns our collective attention to the aural landscape, interrogating the materiality and texture of our sonic worlds. In many ways, The Roaring 'Twenties serves as an extension of Thompson's groundbreaking 2002 book, The Soundscape of Modernity: Architectural Acoustics and the Culture of Listening in America, 1900-1933, but this piece extends that earlier work into new sensory registers and toward new audiences. The project proceeds from a deeply archival impulse. It richly draws from the Municipal Archives of the City of New York, cataloging over 600 unique complaints about noise around 1930 while reproducing over 350 pages of these materials. It also includes fifty-four excerpts of Fox Movietone newsreels, early sound experiments that at once captured and technologically remediated the sounds of New York City, as well as hundreds of other photographs and print materials. Thus, this project brings together a large array of data, but it does not deploy the now-trendy logic of distant reading. Its data is mined through the time-honored techniques of the historian in the archive, through human filtering and detailed close readings. Presented here through a stylized multimedia interface, the piece invites its user to linger with the artifacts and to listen and read with care. The pleasures of this database are not about speed and the algorithm but about a slow and deliberate attention.

The visitor to the piece can navigate along three pathways that organize the site's content via the rubrics of space, time, and sound, each offering a unique vantage point on the database that drives the project. When navigating the spatial pathway, the user can zoom into the various boroughs of the city, locating historical noise complaints throughout the fabric of the metropolitan region. When doing so, the vintage facade of the site is sometimes ruptured, allowing the twenty-first-century styling of Google Maps to burst momentarily onto screen. Similarly, the multi-hued Google logo sits brightly in the lower left corner of the map. These slight temporal ruptures are useful ones, serving as they do to remind us that access to the past is always mediated through the technologies and inquiries of the present, even as it's quite engaging to dwell in the sounds of years gone by.

— Tara McPherson, June 23rd, 2021