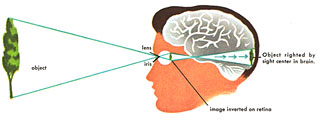

Most of us think of vision as like a camera: When we open our eyes we take a picture of the state of the world as it really is. The world is out there with its objects, colors, textures, shapes and motions whether anyone looks at it or not. The world is, in this sense, independent of us. When we look, vision simply gives us an objective report about this preexisting world.

Malperceptions give us a hint that this pretheoretic idea about how vision works might be very wrong.

Half of your brain's cortex is engaged in vision, in simply opening your eyes and looking at the world. Tens of billions of neurons, trillions of synapes, are employed in your every glance. This is surely overkill for a system that merely take pictures like a camera. What's going on? Why should half of your most intelligent processing power be engaged in simply looking?

Vision isn't simply objective reporting. Instead it is an active process of construction. Your visual system is a reality engine, creating all the objects, colors, motions, textures, and shading that you see. The computational demands of this reality engine are enormous, which is why half of your most intelligent processing power is so engaged.

This also explains the prevalence and variety of malperceptions. With so much cortex engaged in vision, there's a good chance that randomly occurring damage to the brain will have visual consequences, and that these consequences will vary widely depending on the region of the visual system that is impaired. Malperceptions are thus failures of our visual reality engine to construct useful visual worlds.

What about normal perceptions? Does our visual reality engine, the source of our visual perceptions, reliably construct a true description of the objective state of the external world? Evolutionary theory says no. Natural selection shapes perceptions in service of reproduction, not truth. Think of your perceptions as like a windows user interface on your computer. The computer itself is quite complex, with scads of diodes and resistors, and megabytes of software. The windows interface hides this complexity. The interface is useful precisely because it does not resemble the complexity, but hides it behind pretty icons that are easy to manipulate. Our visual experience of a 3D world with objects, colors, shapes and motions is simply a species-specific user interface, shaped by natural selection to allow homo sapiens to survive in its niche. Our perceptions are useful precisely because they do not resemble whatever objectively exists independent of us. Our perceptions give us pretty icons formatted for ease of use and survival, not for truth. We must take our perceptions seriously, but not literally. Don't step in front of a train, just because it is a perceptual icon. Natural selection has made sure that we must take our icons seriously. Malperceptions help us recognize that we cannot take them literally.

Donald Hoffman is a professor of Cognitive Science, Computer Science, and Philosophy at the University of California, Irvine. He received a distinguished scientific award from the American Psychological Association, and the Troland Research Award from the US National Academy of Sciences. He is author of the book Visual Intelligence, published by Norton.